The dying art of bronze, brass - traditional cottage industry in Bangladesh

The traditional cottage industries producing a wide range of bronze and brass goods, once the pride of Chapainawabganj, are now on the verge of extinction as costs of raw materials have multiplied, resulting in higher prices for the products and their dwindling market demand.

Most families involved in the industries have switched over to other professions and many of the craftsmen have turned rickshawpullers and day labourers for survival. Products of the industries include utensils like pitcher, plate, mug, jug, bucket, spoon, pots, bowls and decoration pieces.

"Only a decade ago, almost all families in Azaipur and Shankar Bati areas on the outskirts of the district town used to produce bronze and brass goods, mainly fine utensils. But hardly 10 families still stick to their traditional profession, barely making a living," said Shamsul Huda, a retired primary school teacher of Azaipur area, whose family was involved in the cottage industries.

About the sharp rise in raw materials prices, locals said price of zink has shot up to Tk 1,000 a kg from Tk 330 about six months ago and copper price to Tk 200 per kg from Tk 90. Price of recyclable rejected bronze utensils, locally called Vangri, also rose to Tk 400 a kg from Tk 250 over the same period. This has pushed the price of bronze-made goods to Tk 400 a kg from Tk 250 in wholesale market. Price of brass-made goods has also gone up to around Tk 100 a kg from a much lower price.

"Previously I used to sell about 200 kg of different utensils a day and now I can hardly sell 20 kg. If it continues, I shall have to switch over to other business," said Md Qamruzzaman, who runs a wholesale business of bronze-made goods. Rabiul Islam, who used to make lanterns with bronze and brass, has now become a construction worker. Amirul Islam of Azaipur used to produce bowls but stopped doing it about seven months ago due to the steep rise in raw materials prices.

The British government gazetteer of 1907-1908 said 270 families from both Hindu and Muslim communities in Azaipur and Shankar Bati were involved in this profession. The number of such cottage industries rose to around 500 after the independence of Bangladesh but now their number has come down to less than 100 families, local people said. But aluminium and plastic goods started to compete with these products in the early 80s.

The Lost Art of Metal Casting

The lost-wax technique is an ancient art that dates back over 2,000 years or older in India, China, and Egypt. In the 15th century it was used by the likes of Donatello for the making large-scale bronze nudes. Bowls and plates made with intricate etchings are made using other methods.

Process

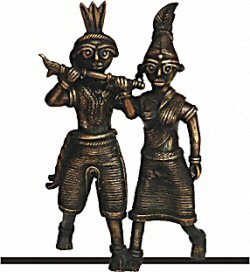

First, the artisan creates a sculpture using wax made from beeswax and paraffin. Three different compositions of river-based clay are then poured over it, two times each. Two nali or openings are molded at one end of each piece. Thirty-six to forty crucibles of brass and bronze metal are arranged at the bottom of a five-foot cylindrical brick oven. Placed over these are the clay molds containing the wax figures. The cylindrical oven is so deep that one of the workmen must go into the oven to lay the raw clay structures. When the crucibles and molds are in place, the oven is fired up. A great mass of smoke rises from the open-top oven, taking the form of a miniature Hiroshima explosion. A 20-foot high flame created by the burning wax discharging from the clay molds eventually replaces the smoke. At this point, the oven has heated between 175-200o centigrade. In the end, none of the wax will remain leaving behind hollow molds. From here arises the term "lost wax". Two and a half-hours after firing up of the oven, the metal starts melting at a scorching 1000o centigrade. Once the metal is liquidified, the scalding hot clay molds are removed from the oven using six-foot long tongs. The empty molds are turned over to expose the nalis and the red-hot molten metal is poured in. After the metal cools down and takes solid form, the outer clay of each mold is chiseled away to reveal a silvery brass statue, a replica of the original wax sculpture. The figure is filed and polished. Lastly, chemicals are added to its surface to give the metal its characteristic patina. The statues are fit for display. Material Most of the figures are made from bronze (a copper and tin alloy) or brass (a copper and zinc alloy). Hindu figures are made out of eight metals believed to have an auspicious connection to the planets. The eight metals are: copper, zinc, tin, iron, lead, mercury, gold and silver.

The Wax Artisan

Once a dying art, metal-casting is being revived by Sukanta Banik, whose business in Dhamrai has been in the family for five generations. Until recently, Banik's forefathers had been making household items with brass and bronze -- kasha and pittal. But in 1971, Sukanta's uncle Shakhi Gopal Banik and his partner, Mosharraf Hossein, changed direction and started producing works of art: figures from Hindu mythology and folk art as well as Buddhist and Jain sculptures.

During Durga Puja season most of the artisans go home to work on clay murtis for their family business. "Wax figures are harder to work on than clay ones because we do replicas of museum designs, but clay murtis are our own creation," says Gautam Pal, the sole remaining artisan of the season.

Designs of the gods and goddesses

Designs of the gods and goddesses are based on the art of the Pala dynasty. They tend to be very intricate, and stand distinguished from statues made elsewhere,

The lost-wax technique allows helps Banik's artisans create more pronounced detailing. In contrast to most Indian statues, whose details are etched onto the solid metal form, the details of one of Banik's statues are made on the soft wax at the initial stages of the sculpting, using soft wax thread, which is then carved into with a bamboo stick. Thus, the embellishments take on a three-dimensional quality.

Murtis from India also differ in that they are usually made from a Master mold.We must attempt to preserve this age-old tradition, not just in Dhamrai, but in other centers like Jamalpur, Islampur, Tangail, Kushtia, and Dhaka." In the words of friend and supporter, Matt Friedman, "If [the metal casting] trade is someday lost, an important part of Bangladesh's artistic tradition will vanish forever." Hats off to Mr. Banik for bringing this decidedly Bangalee tradition back to life (Manisha Gangopadhyay, November 8, 2004).